An Overview of Multi-Task Learning in Speech Recognition

Introduction

The following blog post is a chapter in my dissertation, which I finished in the summer of 2019. The field of Automatic Speech Recognition moves fast, but I think you will find the general trends and logic discussed here to hold true today.

All citations are footnotes, because Markdown ¯\(ツ)/¯

Feel free to leave comments below (especially if you have newer research on Multi-Task Learning for speech!)

Enjoy!

Roadmap

In this overview of Multi-Task Learning in Automatic Speech Recognition (ASR), we’re going to cover a lot of ground quickly. First, we’re going to define Multi-Task Learning and walk through a very simple example from image recognition. Next, once we have an understanding of Multi-Task Learning and we have a definition of “task”, we will move into a survey of the speech recognition literature1.

The literature survey focuses on acoustic modeling in particular. Speech Recognition has a long history, but this blog post is limited in scope to the Hybrid (i.e. DNN-HMM) and End-to-End approaches. Both approaches involve training Deep Neural Networks, and we will focus on how Multi-Task Learning has been used to train them. We will divvy up the literature along monolingual and multilingual models, and then finally we will touch on Multi-Task Learning in other speech technologies such as Speech Synthesis and Speaker Verification.

The term “Multi-Task Learning” encompasses more than a single model performing multiple tasks at inference. Multi-Task Learning can be useful even when there is just one target task of interest. Especially with regards to small datasets, a Multi-Task model can out-perform a model which was trained on just one task.

An Introduction to Multi-Task Learning

Definition

Before we define Multi-Task Learning, let’s first define what we mean by task. Some researchers may define a task as a set of data and corresponding target labels (i.e. a task is merely \((X,Y)\)). Other definitions may focus on the statistical function that performs the mapping of data to targets (i.e. a task is the function \(f: X \rightarrow Y\)). In order to be precise, let’s define a task as the combination of data, targets, and mapping function.

A task is the combination of:

- Data: \(X\), a sample of data from a certain domain

- Targets: \(Y\), a sample of targets from a certain domain

- Mapping Function: \(f: X \rightarrow Y\), a function which maps data to targets

The targets might be distinct label categories represented by one-hot vectors (e.g. classification labels), or they can be \(N\)-dimensional continuous vectors (e.g. a target for regression)2.

Given this definition of task, we define Multi-Task Learning as a training procedure which updates model parameters such that the parameters optimize performance on multiple tasks in parallel3. At its core, Multi-Task Learning is an approach to parameter estimation for statistical models45. Even though we use multiple tasks during training, we will produce only one model. A subset of the model’s parameters will be task-specific, and another subset will be shared among all tasks. Shared model parameters are updated according to the error signals of all tasks, whereas task-specific parameters are updated according to the error signal of only one task.

It is important to note that a Multi-Task model will have both task-dependent and task-independent parameters. The main intuition as to why the Multi-Task approach works is the following: if tasks are related, they will rely on a common underlying representation of the data. Learning related tasks together will bias the shared parameters to encode robust, task-independent representations of the data.

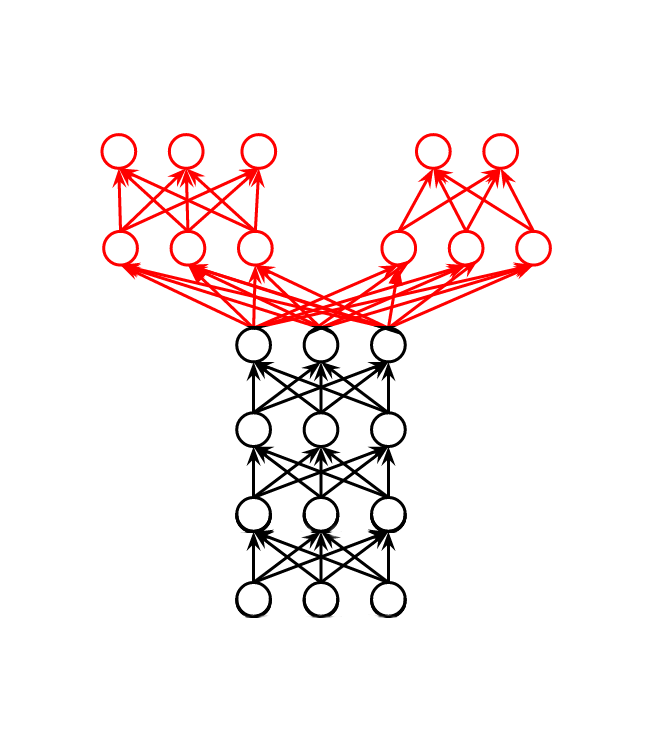

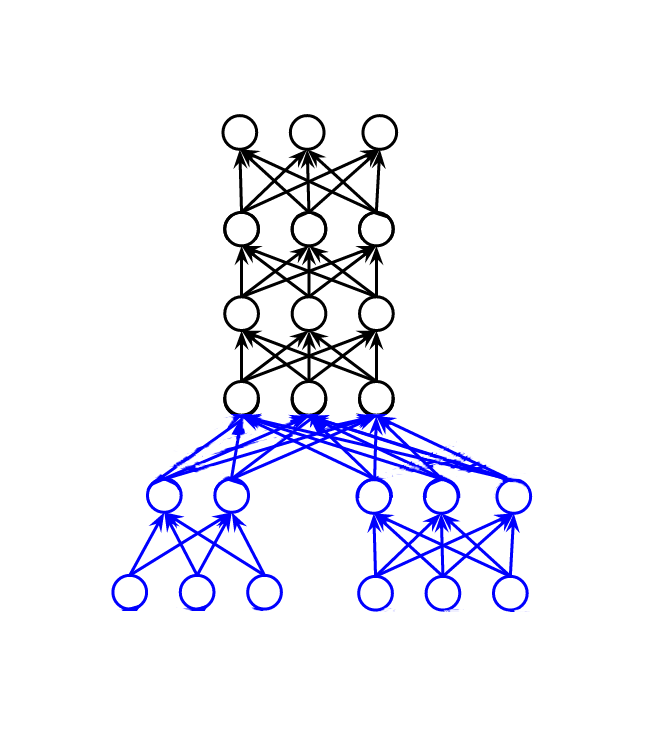

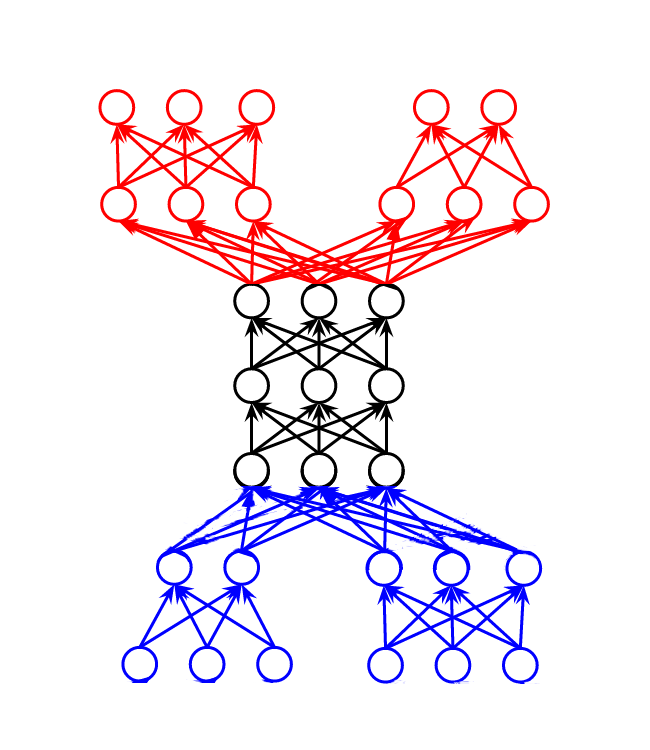

Given this definition of task and this definition of Multi-Task Learning, we can start to think about the different ways in which a Multi-Task model can be trained. Probably the most common Multi-Task use-case is the classification of a single dataset \((X)\) as multiple sets of target labels \((Y_{1}, Y_{2} \dots Y_{N})\). This model will perform mappings from \((X)\) into each of the label spaces separately. Another approach is the classification of multiple datasets sampled from various domains \((X_{1}, X_{2} \dots X_{N})\) as their own, dataset-specific targets \((Y_{1}, Y_{2} \dots Y_{N})\). Less commonly, it is possible to classify multiple datasets using one super-set of labels. These different approaches are represented with regards to vanilla feed-forward neural networks in Figure (1).

With regards to neural approaches (c.f. Figure (1), Multi-Task models are usually comprised of three component parts: (1) shared layers (⬛) which serve as a task-independent feature extractor; (2) task-specific output layers (🟥) which serve as task-dependent classifiers or regressors; (3) task-specific input layers (🟦) which serve as feature transformations from domain-specific to domain-general representations. Neural Multi-Task models will always have some hidden layers shared among tasks. This view of a Multi-Task neural network highlights the intuition behind the shared hidden layers - to encode robust representations of the input data.

With regards to domains in which we have very limited data (i.e. low-resource environments), Multi-Task parameter estimation promises gains in performance which do not require us to collect more in-domain data, as long as we can create new tasks. In the common scenario where an engineer has access to only a small dataset, the best way she could improve performance would be by collecting more data. However, data collection takes time and money. This is the promise of Multi-Task Learning in low-resource domains: if the engineer can create new tasks, then she does not need to collect more data.

An Example of Multi-Task Learning

This section gives an example of a Multi-Task image recognition framework, where we start with a single task, create a second task, and train a model to perform both tasks. Starting with a single task, suppose we have the access to the following:

- Data: \(X_1\), a collection of photographs of dogs from one camera

- Targets: \(Y_1\), a finite set of dog_breed labels (e.g. terrier, collie, rottweiler)

- Mapping Function: \(f_1: X_1 \rightarrow Y_1\), a vanilla feedforward neural network which returns a set of probabilities over labels of dog_breed to a given photograph

In order to create a new task, we either need to collect some data (\(X_2\)) from a new domain, create new targets (\(Y_2\)), or define a new mapping function (\(f_2: X_1 \rightarrow Y_1\)). Furthermore, we would like to create a related task, with the hopes of improving performance on the original task. There’s several ways we can go about making a new task. We could use the same set of labels (dog_breed), but a collect new set of pictures from a different camera. We could try classifying each photograph according to the size of the dog, which would mean we created new labels for our existing data. In addition to our vanilla feed-forward network, we could use a convolutional neural network as a mapping function and share some of the hidden layers between the two networks.

Assuming we don’t want to collect more data and we don’t want to add a new mapping function, the easiest way to create a new task is to create a new set of target labels. Since we only had a single set of labels available (i.e. dog_breed (⬛)), we can manually add a new label to each photo (i.e. dog_size (🟥)) by referencing an encyclopedia of dogs6.

We start with a single dataset of photos of dogs (\(X_1\) (⬛)) and a single set of classification labels (\(Y_1\) (⬛)) for the dog’s breed, and now we’ve added a new set of labels (\(Y_2\) (🟥)) for a classification task of the dog’s size. A few training examples from our training set (\(X_1\) (⬛), \(Y_1\) (⬛), \(Y_2\) (🟥)) may look like what we find in Figure (2).

Given this data and our two sets of labels, we can train a Multi-Task neural network to perform classification of both label sets with the vanilla feed-forward architecture shown in Figure (3). This model now has two task-specific output layers and two task-specific penultimate layers. The input layer and following three hidden layers are shared between both tasks. The shared parameters will be updated via the combined error signal of both tasks.

This example came from image recognition, but now we will move onto to our overview of Multi-Task Learning in Automatic Speech Recognition. As we will see in what follows, researchers have trained Multi-Task Acoustic Models where the auxiliary tasks involve a new data domain, a new label set, or even a new mapping function.

Multi-Task Learning in ASR

The Multi-Task Learning discussed here deals with either acoustic modeling in Hybrid (i.e. DNN-HMM) ASR, or it deals with End-to-End ASR7. The Acoustic Model accepts as input a window of audio features (\(X\)) and returns a posterior probability distribution over phonetic targets (\(Y\)). The phonetic targets can be fine-grained context-dependent units (e.g. triphones from a Hybrid model), or these targets may be simply characters (e.g. as in End-to-End approaches). The following survey will focus on how Multi-Task Learning has been used to train these acoustic models, with a focus on the nature of the tasks themselves.

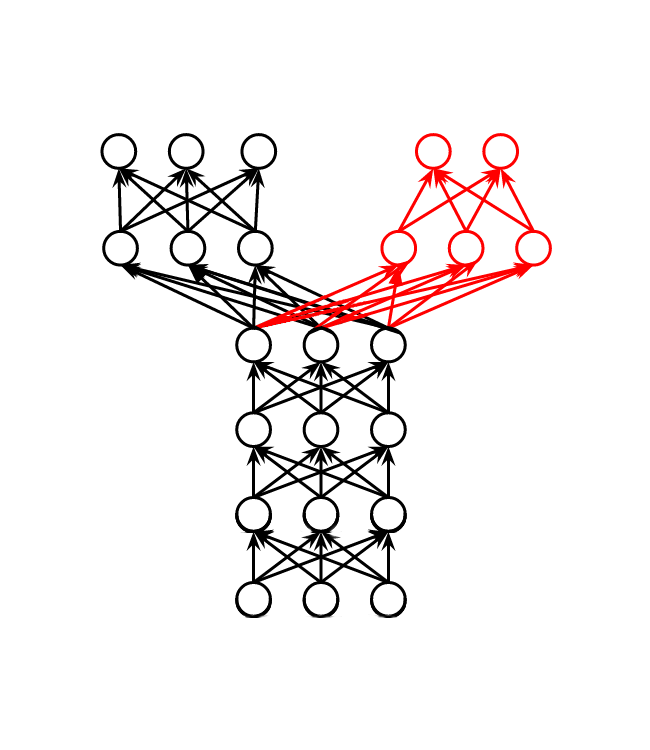

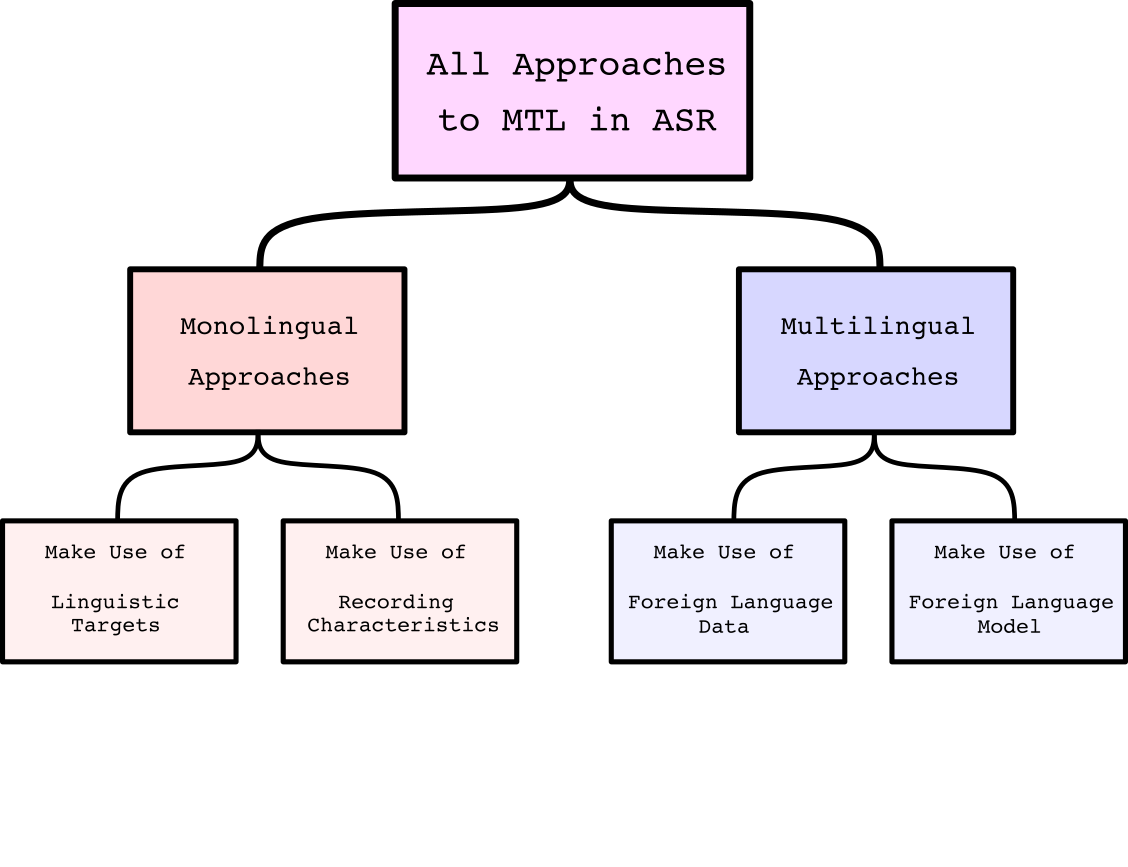

Past work in Multi-Task acoustic modeling for speech recognition can be split into two broad categories, depending on whether data was used from multiple languages or just one language. In this survey, we will refer to these two branches of research as monolingual vs. multilingual approaches. Within each of those two branches, we find sub-branches of research, depending on how the auxiliary tasks are crafted. These major trends are shown in Figure (4), and will be discussed more in-depth below.

Within monolingual Multi-Task acoustic modeling we can identify two trends in the literature. We find that researchers will either (1) predict some additional linguistic representation of the input speech, or (2) explicitly model utterance-level characteristics of the utterance. When using additional linguistic tasks for a single language, each task is a phonetically relevant classification: predicting triphones vs. predicting monophones vs. predicting graphemes8910111213. When explicitly modeling utterance-specific characteristics, researchers either use adversarial learning to force the model to “forget” channel, noise, and speaker characteristics, or the extra task is a standard regression in order to pay extra attention to these features14151617181920212223.

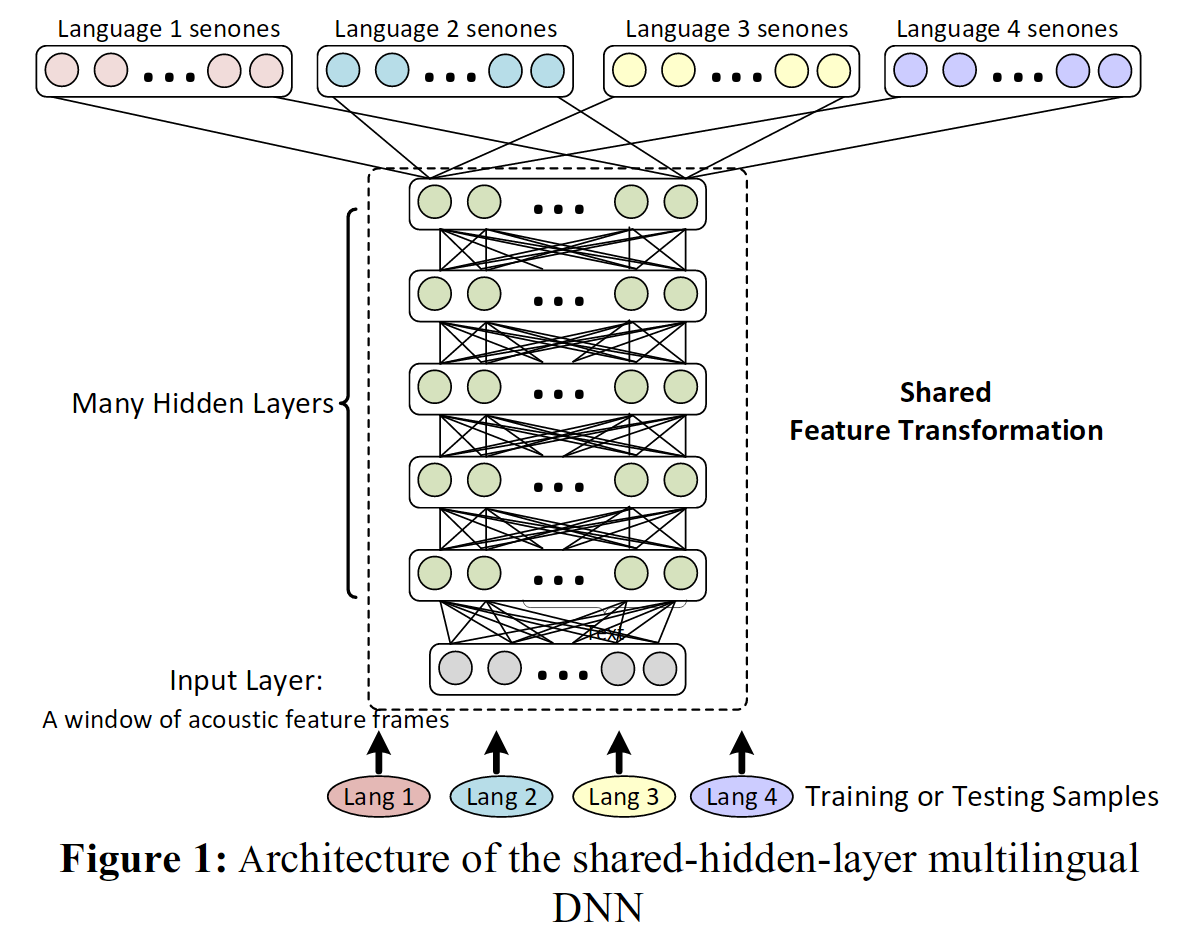

Within multilingual Multi-Task acoustic modeling we can also identify two main veins of research: (1) using data from some source language(s) or (2) using a pre-trained model from some source language(s). When using data from source languages, most commonly we find researchers training a single neural network with multiple output layers, where each output layer represents phonetic targets from a different language24252627282930313219. As such, these Acoustic Models look like the prototype shown in Figure (1a). When using a pre-trained model from some source language(s) we find researchers using the source model as either a teacher or as a feature extractor for the target language33343536373839. The source model extracts embeddings of the target speech, and then the embedding is either used as the target for an auxiliary task or the embedding is concatenated to the standard input as a kind of feature enhancement.

Monolingual Multi-Task ASR

With regards to monolingual Multi-Task Learning in ASR, we find two major tracks of research. The first approach is to find tasks (from the same language) which are linguistically relevant to the main task4091084111124243444546. These studies define abstract phonetic categories (e.g. fricatives, liquids, voiced consonants), and use those category labels as auxiliary tasks for frame-level classification.

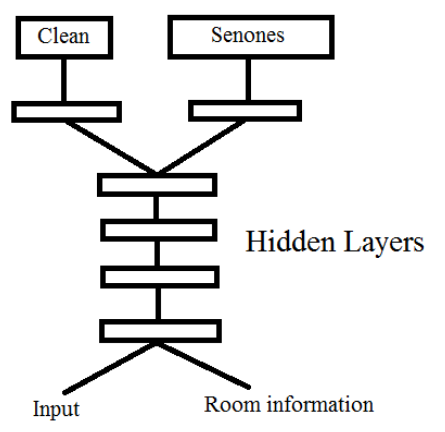

The second major track of research in monolingual Multi-Task acoustic modeling involves explicit modeling of speaker, channel, or noise characteristics14151617181920212223. These studies train the Acoustic Model to identify these characteristics via an additional classification task, or they encourage the model to ignore this information via adversarial learning, or they force the model to map data from the input domain to another domain (e.g. from noisy audio \(\rightarrow\) clean audio).

All the studies in this section have in common the following: the model in question learns an additional classification of the audio at the frame-level. That is, every chunk of audio sent to the model will be mapped onto a standard ASR category such as a triphone or a character in addition to an auxiliary mapping which has some linguistic relevance. This linguistic mapping will typically be a broad phonetic class (think vowel vs. consonant) of which the typical target (think triphone) is a member.

Good examples of defining additional auxiliary tasks via broad, abstract phonetic categories for English can be found in Seltzer (2013)9 and later Huang (2015)10. With regards to low-resource languages, some researchers have created extra tasks using graphemes or a universal phoneset as more abstract classes111242.

A less linguistic approach, but based on the exact same principle of using more abstract classes as auxiliary targets, Bell (2015)8 used monophone alignments as auxiliary targets for DNN-HMM acoustic modeling (in addition to the standard triphone alignments). The authors observed that standard training on context-dependent triphones could easily lead to over-fitting on the training data. When monophones were added as an extra task, they observed \(3-10\%\) relative improvements over baseline systems. The intuition behind this approach is that two triphones belonging to the same phoneme will be treated as completely unrelated classes in standard training by backpropagation. As such, valuable, exploitable information is lost. In follow up studies, these studies434445 made the linguistic similarities among DNN output targets explicit via linguistic phonetic concepts such as place, manner, and voicing as well as phonetic context embeddings.

However, the benefits of using linguistic targets vary from study to study, and in their survey paper, Pironkov (2016)46 concluded that “Using even broader phonetic classes (such as plosive, fricative, nasal, \(\ldots\)) is not efficient for MTL speech recognition”. In particular, they were referring to the null findings from Stadermann (2015)40.

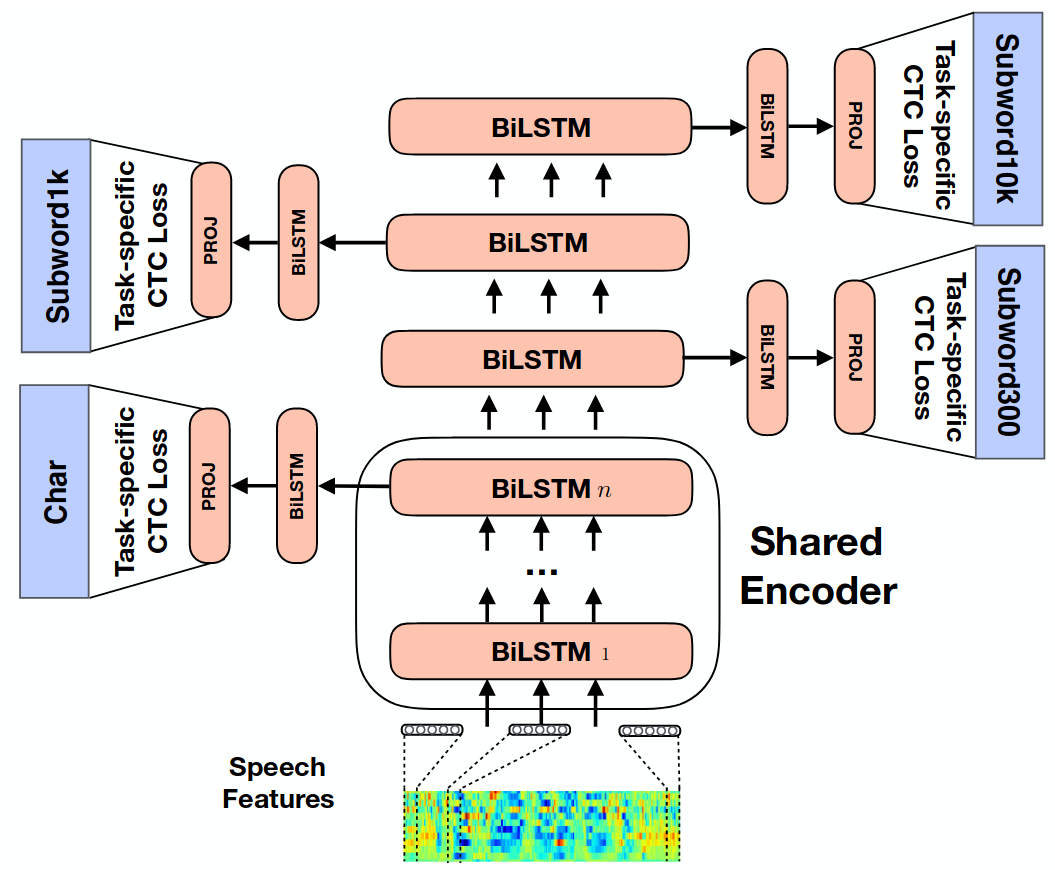

In a similar vein, Multi-Task Learning has been used in an End-to-End framework, in an effort to encourage explicit learning of hierarchical structure of words and phonemes. Oftentimes these hierarchical phonemic levels (e.g. phonemes vs. words) are trained at different levels of the model itself4748491350. Figure (5) displays the approach taken in Sanabria (2018)48.

All of these studies have in common the following: they encourage the model to learn abstract linguistic knowledge which is not explicitly available in the standard targets. Whatever the standard target may be (e.g. triphones, graphemes, etc.) the researchers in this section created abstract groupings of those labels, and used those new groupings as an additional task. These new groupings (e.g. monophones, sub-word units, etc) encourage the model to learn the set of underlying features (e.g. voicing, place of articulation, etc.) which distinguish the main targets.

Regression on Better Features as a new Task

Class labels are the most common output targets for an auxiliary task, but the authors in 20212223 took an approach where they predicted de-noised versions of the input audio from noisy observations (c.f. Figure (6)). The effect of this regression was that the Acoustic Model cleaned and classified each input audio frame in real time.

In a similar vein, Das (2017)51 trained an Acoustic Model to classify standard senomes targets as well as regress an input audio frame to bottleneck features of that same frame. Bottleneck features are a compressed representation of the data which have been trained on some other dataset or task — as such bottleneck features should contain linguistic information. In a very early study, the authors in Lu (2004)52 predicted enhanced audio frame features as an auxiliary task (along with the speaker’s gender).

Extra Mapping Function as New Task

In End-to-End ASR, Kim (2017)53 created a Multi-Task model by adding a mapping function (CTC) to an attention-based encoder-decoder model. This is an interesting approach because the two mapping functions (CTC vs. attention) carry with them pros and cons, and the authors demonstrate that the alignment power of the CTC approach can be leveraged to help the attention-based model find good alignments faster. Along similar lines, Lu (2017)54 trained an Acoustic Model to make use of both CTC and Sequential Conditional Random Fields. These works did not create new labels or find new data, but rather, they combined different alignment and classification techniques into one model.

A famous example of monolingual MTL using multiple mapping functions is the most common Kaldi implementation of the so-called “chain” model55. This implementation uses different output layers on a standard feed-forward model, one output layer calculating standard Cross Entropy Loss, and the other calculating a version of the Maximum Mutual Information Criterion.

New Domain as New Task

If we consider the different characteristics of each recording as domain memberships, then any extra information we have access to (e.g. age, gender, location, noise environment), can be framed as domain information, and this information can be explicitly modeled in a Multi-Task model. Using a Multi-Task adversarial framework, these studies141516 taught an Acoustic Model to forget the differences between different noise conditions, these studies1718 taught their model to forget speakers, and Sun (2018)19 taught the model to forget accents.

In low-resource domains, it is often tempting to add data from a large, out-of-domain dataset into the training set. However, if the domains are different enough a mixed training set may hurt performance more than it helps. Multi-Task Learning lends itself well to these multi-domain scenarios, allowing us to regulate how much influence the out-of-domain data has over parameter estimation during training. Usually we will want to down-weight the gradient from a source domain task if the source dataset is large or if the task is only somewhat related.

The researchers in Qin (2018)56 investigated the low-resource domain of Cantonese aphasic speech. Using a small corpus of aphasic Cantonese speech in addition to two corpora of read Cantonese speech, the researchers simply trained a Multi-Task model with each corpus as its own task (i.e. data from each corpus as classified in its own output layer). Similarly, in an effort to better model child-speech in a low-resource setting, the authors in Tong (2017)57 created separate tasks for classification of child vs. adult speech, in addition to standard phoneme classification.

Discussion of Monolingual Multi-Task Learning

In this section we’ve covered various examples of how researchers have incorporated Multi-Task Learning into speech recognition using data from a single language. Two major threads of work can be identified: (1) the use of abstract linguistic features as additional tasks, or (2) the use of speaker and other recording information as an extra task.

With regards to the first track of work, researchers have created abstract linguistic target labels by defining linguistic categories by hand, by referring to the traditional phonetic decision tree, or by automatically finding relevant sub-word parts. Performance improvements with this approach have been found to be larger when working with small datasets4342. The intuition behind this line of work is the following: Forcing a model to classify input speech into broad linguistic classes should encourage the model to learn a set of underlying phonetic features which are useful for the main classification task.

A discriminative Acoustic Model trained on standard output targets (e.g. triphones, characters) is trained to learn that each target is maximally different from every other target. The label-space at the output layer is N-dimensional, and every class (i.e. phonetic category) occupies a corner of that N-dimensional space. This means that classes are learned to be maximally distinctive. In reality, we know that some of these targets are more similar than others, but the model does not know that. Taking the example of context-dependent triphones, the Acoustic Model does not have access to the knowledge that an [a] surrounded by [t]’s is the same vowel as an [a] surrounded by [d]’s. In fact, these two [a]’s are treated as if they belong to completely different classes. It is obvious to humans that two flavors of [a] are more similar to each other than an [a] is similar to an [f]. However, the output layer of the neural net does not encode these nuances. Discriminative training on triphone targets will loose the information that some triphones are more similar than others. One way to get that information back is to explicitly teach the model that two [a] triphones belong to the same abstract class. This is the general intuition behind this first track of monolingual Multi-Task work in speech recognition.

The second track of monolingual Multi-Task acoustic modeling involves explicit modeling of speaker, noise, and other recording characteristics via an auxiliary task. While all of these variables are extra-linguistic, studies have shown that either paying extra attention to them (via an auxiliary classification task) or completely ignoring them (via adversarial learning) can improve overall model performance in terms of Word Error Rate. This is a somewhat puzzling finding. Learning speaker information5258 can be useful, but also forgetting speaker information1718 can be useful.

If we think of why this may be the case, we can get a little help from latent variable theory. If we think of any recording speech as an observation that has been generated by multiple underlying variables, we can define some variables which generated the audio, such as (1) the words that were said, (2) the speaker, (3) the environmental noise conditions, (4) the acoustics of the recording location, and many, many others. These first four factors are undoubtedly influencers in the acoustic properties of the observed recording. If we know that speaker characteristics and environmental noise had an influence on the audio, then we should either explicitly model them or try to remove them altogether. Both approaches show improvement over a baseline which chooses to not model this extra information at all, but as discovered in Adi (2018)59, if the dataset is large enough, the relative improvements are minor.

Multilingual Multi-Task ASR

Multilingual Multi-Task ASR can be split into two main veins, depending on whether (1) the data from a source language is used or (2) a trained model from the source language is used. We find that the first approach is more common, and researchers will train Acoustic Models (or End-to-End models) with multiple, task-dependent output layers (i.e. one output layer for each language), and use the data from all languages in parameter estimation. These models typically share the input layer and all hidden layers among tasks, creating a kind of language-universal feature extractor. This approach has also been extended from multiple languages to multiple accents and dialects. The second vein of multilingual Multi-Task Learning involves using an Acoustic Model from one language as a teacher to train an Acoustic Model from some target language. Most commonly, this source model can be used to generate phoneme-like alignments on the target language data, which are in turn used as targets in an auxiliary task. More often than not, we find multilingual Multi-Task approaches used in a low-resource setting.

Multiple Languages as Multiple Tasks

The earliest examples of Multi-Task Learning with multiple languages can be found in Huang (2013)24 and Heigold (2013)25 (c.f. Figure (7)). These studies focused on improving performance on all languages found in the training set, not just one target language. Every language was sampled to the same audio features, and as such the neural networks only required one input layer. However, the network was trained to classify each language using language-specific phoneme targets. Taking this line of research into the world of End-to-End speech recognition, Dalmia (2018)60 showed that a CTC model trained on multiple languages, and then tuned to one specific language can improve performance over a model trained on that one language in a low-resource setting.

In a similar vein of work, instead of optimizing performance on all languages present in the training set, researchers have aimed to perform best on one particular target language. See Wang (2015)61 for a survey of advances in this area.

Addressing the use-case where audio is available for a target language, but native-speaker transcribers are not easy to find, Do (2017)62 employed non-native speakers to transcribe a target language into non-sense words, according to how they perceived the language. Using these non-native transcriptions in addition to a small set of native-speaker transcripts, the authors trained a Multi-Task model to predict phonemes from both native or non-native transcripts. The intuition as to why this approach works is that non-native speakers will perceive sounds from a foreign language using their native phonemic system, and enough overlap should exist between the two languages to help train the acoustic model.

In the relatively new field of spoken language translation, where speech from one language is mapped directly to a text translation in a second language, these researchers6364 created multiple auxiliary tasks by either recognizing the speech of the source language (i.e. standard ASR), or by translating the source language into one or more different languages.

Multiple Accents as Multiple Tasks

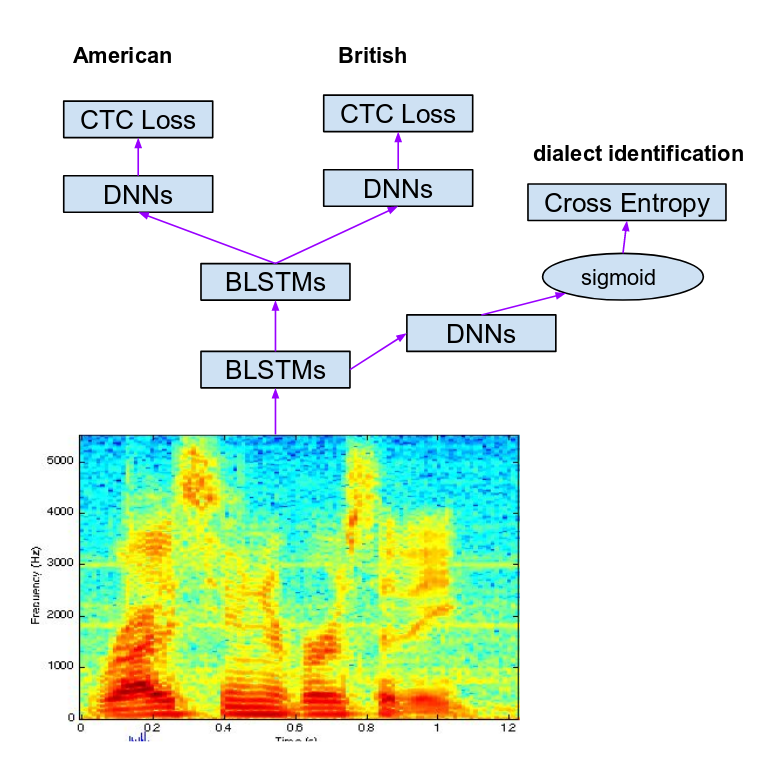

In a vein of research which belongs somewhere between monolingual and multilingual speech recognition, the authors in 30313219 used Multi-Task Learning to perform multi-accent speech recognition. The researchers in Yang (2018)30 trained a model to recognize English, with separate output layers for British English vs. American English. These two tasks were trained in parallel with a third task, accent identification. Combining all three tasks led to optimal output (c.f. Figure (8)). The authors in Rao (2017)31 recognized phonemes of different English accents at an intermediate hidden layer, and then accent-agnostic graphemes at the output layer.

Multilingual Model as Feature Extractor

So-called bottleneck features have also been developed to aid in low-resource acoustic modeling, which often incorporate Multi-Task Learning. These bottleneck features are activations from a condensed hidden layer in a multilingual acoustic model. First a multilingual Acoustic Model is trained, and then data from a new language is passed through this DNN, and the bottleneck activations are appended as additional features to the original audio333435363738. In this way, a kind of universal feature extractor is trained on a large multilingual dataset. The bottleneck features themselves are the product of Multi-Task Learning.

Source Language Model as Teacher

Instead of using data from multiple languages, it is possible to use the predictions from a pre-trained source model as targets in an auxiliary task. In this way, knowledge located in the source dataset is transferred indirectly via a source model, as opposed to directly from the dataset itself.

In a very recent approach, He (2018)39 trained a classifier on a well-resourced language to identify acoustic landmarks, and then used that well-resourced model to identify acoustic landmarks in a low-resourced language. Those newly discovered acoustic landmarks were then used as targets in an auxiliary task. This approach can be thought of as a kind of Multi-Task Student-Teacher (c.f. Wong (2016)65) approach, where we “distill” (c.f. Hinton (2015)66) knowledge from one (larger) model to another via an auxiliary task.

Discussion of Multilingual Multi-Task Learning

Surveying the literature of Multi-Task Learning in multilingual speech recognition, we can identify some common findings among studies. Firstly, we observe positive effects of pooling of as many languages as possible, even when the languages are completely unrelated. This pooling of unrelated languages may seem strange at first - why should languages as different as English and Mandarin have anything in common? However, abstracting away from the linguistic peculiarities of each language, all languages share some common traits.

All spoken languages are produced with human lungs, human mouths, and human vocal tracts. This means that all languages are produced in an acoustic space constrained by the anatomy of the human body. If we can bias a model to search for relevant patterns only within this constrained space, then we should expect the model to learn useful representations faster. Likewise, the model should be less likely to learn irrelevant correlated information about environmental noise which occurs outside this humanly-producible acoustic space. This is one intuition as to why the combination of unrelated languages is helpful: any extra language will add inductive bias for the relevant search space of human speech sounds.

Nevertheless, these studies do show a tendency that closely related languages help each other more than unrelated languages. Both Huang (2013)24 and Dalmia (2018)60 concluded that improvement was greater when the languages were more similar. However, they still found that phonetically distinct languages were able to transfer useful bias to each other when a large enough dataset was used for the source language. With regards to how much Multi-Task Learning helps relative to size of the target language dataset, the authors in Heigold (2013)25 and Huang (2013)24 saw larger relative improvements when the dataset for the target language was smaller (but they still observed improvements on large datasets).

In conclusion, Multi-Task Learning for multilingual acoustic modeling yields largest improvements when: (1) the dataset for the target language is small, (2) the auxiliary language is closely related, and (3) the auxiliary language dataset is large.

Multi-Task Learning in Other Speech Technologies

In addition to Automatic Speech Recognition, Multi-Task Learning has found its way into other speech technologies. The use of Multi-Task Learning is less established in the following speech technology fields, and as such we find a very interesting mix of different applications and approaches.

Speech Synthesis

Working on speech synthesis, the research team in Hu (2015)67 used Multi-Task Learning to train neural speech synthesis systems for a single language. These models predicted both the acoustic features (spectral envelope) as well as log amplitude of the output speech. Additionally, these researchers recombined the outputs of both tasks to improve the quality of the final synthesized speech. In a similar vein, authors in Wu (2015)68 employed Multi-Task Learning of vocoder parameters and a perceptual representation of speech (along with bottleneck features) to train a deep neural network for speech synthesis. Working with input features which are not speech or text, but rather ultrasonic images of tongue contours, the authors in Toth (2018)69 trained a model to perform both phoneme classification as well as regression on the spectral parameters of a vocoder, leading to better performance on both tasks. Recently, in their work on modeling the raw audio waveform, the authors in Gu (2018)70 trained their original WaveNet model to predict frame-level vocoder features as a secondary task.

Speech Emotion Recognition

Working on emotion recognition from speech, Parthasarathy (2017)71 demonstrate that a model can be used to identify multiple (believed to be orthogonal) emotions as separate tasks. The authors in Le (2017)72 take an emotion recognition task which is typically a regression, and discover new, discrete targets (via k-means clustering) to use as targets in later auxiliary tasks. Using classification of “gender” and “naturalness” as auxiliary tasks, Kim (2017)73 also found improvements in spoken emotion recognition via Multi-Task training. Recently, the authors in Lotfian (2018)74 trained a model to predict the first and second most salient emotions felt by the evaluator.

Speaker Verification

With regards to speaker verification, the authors in Liu (2018)75 used phoneme classification as an auxiliary task, and the authors in Ding (2018)76 trained speaker embeddings by jointly optimizing (1) a GAN to distinguish speech from non-speech and (2) a speaker classifier.

Combing both speech recognition and speaker verification, Chen (2015)58 trained an Acoustic Model to perform both tasks and found improvement. In an adversarial framework, Wang (2018)77 taught their model to forget the differences between domains in parallel to identifying speakers.

Miscellaneous Speech Applications

Extending the work from Multi-Task speech recognition to Key-Word Spotting, the researchers in Panchapagesan (2016)78 combined parameter-copying and MTL. They first took an Acoustic Model from large-vocabulary English recognition task, re-initialized the weights immediately proceeding the output layer, and retrained with two output layers. One layer predicted only the phonemes in the Key-Word of interest, and another layer predicted senomes from the large vocabulary task.

To predict turn-taking behavior in conversation, the authors in Hara (2018)79 trained a model to jointly predict backchannelling and use of filler words.

Predicting the severity of speech impairment (i.e. dysarthia) in the speech of patients with Parkinson’s disorder, the researchers in Vasquez (2018)80 trained a model to predict the level of impairment in various articulators (e.g. lips, tongue, larynx, etc.) as multiple tasks.

The researchers in Xu (2018)81 trained a model to both separate speech (from a multi-speaker monaural signal) in addition to an auxiliary task of classifying every audio frame as single-speaker vs. multi-speaker vs. no-speaker.

The researchers in He (2018)82 trained a model to both localize speech sources as well as classify incoming audio as speech vs. non-speech.

Conclusion

In this survey we touched on the main veins of Multi-Task work in speech recognition (as well as other speech technologies). With regards to speech recognition, we identified multilingual and monolingual trends. Multilingual approaches exploit bias from a source language by using a source dataset or a pre-trained source model. Monolingual approaches use targets either at the acoustic frame level or at the recording level. All approaches involve the updating of task-dependent and task-independent parameters. We find it is often the case that Multi-Task Learning is applied to low-resource scenarios, where bias from related tasks can be crucial for successful model training.

References & Footnotes

-

For a more complete overview of Multi-Task Learning itself: Ruder (2017) ↩

-

These two kinds of targets are the same with regards to training neural networks via backpropagation. The targets for classification are just a special case of regression targets, where the values in the vector are \(1.0\) or \(0.0\). ↩

-

An exception to this is Multi-Task Adversarial Learning, in which performance on an auxiliary task is encouraged to be as poor as possible. In domain adaptation, an example of this may be forcing a neural net to be blind to the difference between domains. The Adverserial auxiliary task would be classification of domain-type, and the weights would be updated in a way to increase error as much as possible. ↩

-

Caruana (1998): Multitask learning ↩

-

Caruana (1996): Algorithms and applications for Multitask Learning ↩

-

This is an example of using domain or expert knowledge to create a new task, where the expert knowledge is contained in the encyclopedia. One could also hire a dog expert to label the images manually. Either way, we are exploiting some source of domain-specific knowledge (i.e. knowledge of the physiology of different dog breeds). ↩

-

In the traditional, Hybrid ASR approach (i.e. DNN Acoustic Model + N-gram language model), there’s not a lot of room to use MTL when training the language model or the decoder. ↩

-

Bell (2015): Regularization of context-dependent deep neural networks with context-independent multi-task training ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Seltzer (2013): Multi-task learning in deep neural networks for improved phoneme recognition ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Huang (2015): Rapid adaptation for deep neural networks through multi-task learning ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Chen (2014): Joint acoustic modeling of triphones and trigraphemes by multi-task learning deep neural networks for low-resource speech recognition ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Chen (2015): Multitask Learning of Deep Neural Networks for Low-resource Speech Recognition ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Toshniwal (2017): Multitask Learning with Low-Level Auxiliary Tasks for Encoder-Decoder Based Speech Recognition ↩ ↩2

-

Shinohara (2016): Adversarial Multi-Task Learning of Deep Neural Networks for Robust Speech Recognition ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Serdyuk (2016): Invariant representations for noisy speech recognition ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Tripathi (2018): Adversarial Learning of Raw Speech Features for Domain Invariant Speech Recognition ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Saon (2017): English conversational telephone speech recognition by humans and machines ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4

-

Meng (2018): Speaker-invariant training via adversarial learning ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4

-

Sun (2018): Domain Adversarial Training for Accented Speech Recognition ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5

-

Parveen (2003): Multitask learning in connectionist robust ASR using recurrent neural networks ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Giri (2015): Improving speech recognition in reverberation using a room-aware deep neural network and multi-task learning ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Chen (2015): Speech enhancement and recognition using multi-task learning of long short-term memory recurrent neural networks ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Zhang (2017): Attention-based LSTM with Multi-task Learning for Distant Speech Recognition ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Huang (2013): Cross-language knowledge transfer using multilingual deep neural network with shared hidden layers ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4

-

Heigold (2013): Multilingual acoustic models using distributed deep neural networks ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Tuske (2014): Multilingual MRASTA features for low-resource keyword search and speech recognition systems ↩

-

Mohan (2015): Multi-lingual speech recognition with low-rank multi-task deep neural networks ↩

-

Grezl (2016): Boosting performance on low-resource languages by standard corpora: An analysis ↩

-

Matassoni (2018): Non-Native Children Speech Recognition Through Transfer Learning ↩

-

Yang (2018): Joint Modeling of Accents and Acoustics for Multi-Accent Speech Recognition ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Rao (2017): Multi-accent speech recognition with hierarchical grapheme based models ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Jain (2018): Improved Accented Speech Recognition Using Accent Embeddings and Multi-task Learning ↩ ↩2

-

Dupont (2015): Feature extraction and acoustic modeling: an approach for improved generalization across languages and accents ↩ ↩2

-

Cui (2015): Multilingual representations for low resource speech recognition and keyword search ↩ ↩2

-

Grezl (2014): Adaptation of multilingual stacked bottle-neck neural network structure for new language ↩ ↩2

-

Knill (2013): Investigation of multilingual deep neural networks for spoken term detection ↩ ↩2

-

Vu (2014): Multilingual deep neural network based acoustic modeling for rapid language adaptation ↩ ↩2

-

Xu (2015): A comparative study of BNF and DNN multilingual training on cross-lingual low-resource speech recognition ↩ ↩2

-

He (2018): Improved ASR for Under-Resourced Languages Through Multi-Task Learning with Acoustic Landmarks ↩ ↩2

-

Stadermann (2005): Multi-task learning strategies for a recurrent neural net in a hybrid tied-posteriors acoustic mode ↩ ↩2

-

Arora (2017): Phonological feature based mispronunciation detection and diagnosis using multi-task DNNs and active learning ↩

-

Chen (2015): Multi-task Learning Deep Neural Networks for Automatic Speech Recognition ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Bell (2015): Complementary tasks for context-dependent deep neural network acoustic models ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Swietojanski (2015): Structured output layer with auxiliary targets for context-dependent acoustic modelling ↩ ↩2

-

Badino (2016): Phonetic Context Embeddings for DNN-HMM Phone Recognition ↩ ↩2

-

Pironkov (2016): Multi-task learning for speech recognition: an overview ↩ ↩2

-

Fernandez (2007): Sequence labelling in structured domains with hierarchical recurrent neural networks ↩

-

Sanabria (2018): Hierarchical Multi-Task Learning With CTC ↩ ↩2

-

Krishna (2018): Hierarchical Multitask Learning for CTC-based Speech Recognition ↩

-

Moriya (2018): Multi-task Learning with Augmentation Strategy for Acoustic-to-word Attention-based Encoder-decoder Speech Recognition ↩

-

Das (2017): Deep Auto-encoder Based Multi-task Learning Using Probabilistic Transcriptions ↩

-

Lu (2004): Multitask learning in connectionist speech recognition ↩ ↩2

-

Kim (2017): Joint CTC-attention based end-to-end speech recognition using Multi-Task Learning ↩

-

Lu (2017): Multitask Learning with CTC and Segmental CRF for Speech Recognition ↩

-

Povey (2016): Purely Sequence-Trained Neural Networks for ASR Based on Lattice-Free MMI ↩

-

Qin (2018): Automatic Speech Assessment for People with Aphasia Using TDNN-BLSTM with Multi-Task Learning ↩

-

Tong (2017): Multi-Task Learning for Mispronunciation Detection on Singapore Children’s Mandarin Speech ↩

-

Chen (2015): Multi-task learning for text-dependent speaker verification ↩ ↩2

-

Adi (2018): To Reverse the Gradient or Not: An Empirical Comparison of Adversarial and Multi-task Learning in Speech Recognition ↩

-

Dalmia (2018): Sequence-based Multi-lingual Low Resource Speech Recognition ↩ ↩2

-

Wang (2015): Transfer learning for speech and language processing ↩

-

Do (2017): Multi-task learning using mismatched transcription for under-resourced speech recognition ↩

-

Weiss (2017): Sequence-to-Sequence Models Can Directly Transcribe Foreign Speech ↩

-

Anastasopoulos (2018): Tied Multitask Learning for Neural Speech Translation ↩

-

Wong (2016): Sequence student-teacher training of deep neural networks ↩

-

Hinton (2015): Distilling the knowledge in a neural network ↩

-

Hu (2015): Fusion of multiple parameterisations for DNN-based sinusoidal speech synthesis with multi-task learning ↩

-

Wu (2015): Deep neural networks employing multi-task learning and stacked bottleneck features for speech synthesis ↩

-

Toth (2018): Multi-Task Learning of Speech Recognition and Speech Synthesis Parameters for Ultrasound-based Silent Speech Interfaces ↩

-

Gu (2015): Multi-task WaveNet: A Multi-task Generative Model for Statistical Parametric Speech Synthesis without Fundamental Frequency Conditions ↩

-

Parthasarathy (2017): Jointly predicting arousal, valence and dominance with multi-task learning ↩

-

Le (2017): Discretized continuous speech emotion recognition with multi-task deep recurrent neural network ↩

-

Kim (2017): Towards Speech Emotion Recognition in the wild using Aggregated Corpora and Deep Multi-Task Learning ↩

-

Lotfian (2018): Predicting Categorical Emotions by Jointly Learning Primary and Secondary Emotions through Multitask Learning ↩

-

Liu (2018): Speaker Embedding Extraction with Phonetic Information ↩

-

Ding (2018): MTGAN: Speaker Verification through Multitasking Triplet Generative Adversarial Networks ↩

-

Wang (2018): Unsupervised domain adaptation via domain adversarial training for speaker recognition ↩

-

Panchapagesan (2016): Multi-Task Learning and Weighted Cross-Entropy for DNN-Based Keyword Spotting ↩

-

Hara (2018): Prediction of Turn-taking Using Multitask Learning with Prediction of Backchannels and Fillers ↩

-

Vasquez (2018): A Multitask Learning Approach to Assess the Dysarthria Severity in Patients with Parkinson’s Disease ↩

-

Xu (2018): A Shifted Delta Coefficient Objective for Monaural Speech Separation Using Multi-task Learning ↩

-

He (2018): Joint Localization and Classification of Multiple Sound Sources Using a Multi-task Neural Network ↩